The experimental legacy

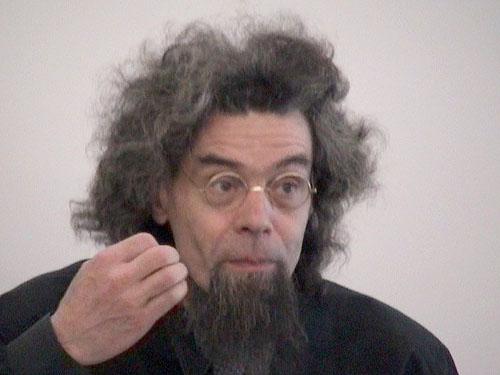

dr.Godfried-Willem Raes

postdoctoral researcher

Orpheus Institute & Logos Foundation

2015-2023

an introduction

Landed in the second decennium of the 21st century we can start to look back on the 20th century as part of history. As usual long known problems are encountered. A fundamental question will always be what to preserve. Selections have to be made and criteria justified. Even if we don't do anything, leaving things as they are, entropy will guarantee a form of selection. Think about electronic music made on analog tape. We know that preserving those tapes poses a manifold of problems. Not only the carriers deteriorate, but also the machines to play them and to make copies to other media are more and more difficult to find and to maintain in full operating condition. The technology of the pre-digital era is no longer commonly available to electronic engineers. Repairman are by now all if not dead, at least retired or no longer capable to properly do maintenance and repair. The components once used are since long no longer made nor findable on the market. Moreover, even if important tapes from the archives were transferred to CD's, we now observe that these CD's are rapidly becoming unplayable. Entropy cannot be circumvented it seems, at the most we can slow it down.

Looking at the music of the 20th century, the problems we encounter can be of very different nature:

1. Music that was composed and conceived for technological tools that at the time of the conception of their use just couldn't fill the promises.

Some examples:

From the first half of the 20th century:

- Georges Antheil, 'Ballet Mecanique' (player piano synchronisation, propellers, sirens, electric bells...)

- Igor Strawinsky ' Les Noces' (player piano synchronisation)

- Kurt Weill 'Dreigrosschenoper' (for barrelorgan as first proposed by Bertold Brecht)

- Leopold Stochowsky: theremin instruments in the orchestra

From the second half of the 20th century

- Karlheinz Stockhausen 'Solo mit Rueckkopplung'

- Alvin Lucier, pieces involving brainwaves

- Dick Raaijmakers 'Elektries Strijkkwartet'

- Conlon Nancarrow 'Player piano studies', percussion extensions

In these cases musicologists are often tempted to consider the work eventually revised later by the composer, as the definitive work. Here we can raise the question whether it wouldn't do more justice to the composer to get back to his original concepts and try to realize them with what technology permits us to do today. In this line of thinking, at Logos we did a version of Noces using only automated instruments, we realized Ballet Mecanique with real airplane propellers, modern player pianos, automated sirens and industrial bells and in 2016 we finished and presented a version of Kurt Weills Beggars Opera using our complete robot orchestra, thus realising the original concept of Bertolt Brecht.

Other people have realized 'Solo mit Rueckkopplung' using digital technology, thus not plagued by the inherent instability of long analog tape loops on stage. As to Dick Raaijmakers 'elektries strijkkwartet', we made a working version whilst the composer was still alive. A report can be found here (as yet only in dutch). Some biographical data with regard to Raaijmakers can be found here.

2. Music making use of technology that is no longer available or in need of maintenance and repair.

The crucial question here is in how far the technology used is an essential part of the rhetoric of the performance. This is not always the case. For instance the thousands of compositions written for tape and musicians, do not require the reel to reel taperecorder as an essential component of performance and for such pieces, playing the on-tape sound track from just about any modern medium (CD or simply from the computers memory) does not change anything to the performance. However, there are many examples of pieces where the tape recorder becomes an instrument in itself, more than merely a reproducing device.

Example:

Alvin Lucier's pieces using slow sweep sine wave oscillators

Brian Ferneyhough and Karlheinz Stockhausen's pieces involving ring modulators

Pieces involving live manipulation of audio tape and tape recorders: Dick Raaymakers, Michel Waisvisz, Brian Ferneyhough, Steven Montague, Gordon Mumma, Pauline Oliveros, John Cage...

Pieces involving manual handling of electronic circuitry and components: John Cage, David Behrman, David Tudor, Gordon Mumma, Dick Raaijmakers, Michel Waisvisz, Takehisa Kosugi, Larry Wendt, Allan Strange, Ron Kuivila, Nam Yun Paik

In these cases it appears to us to be pointless to replace the technology used with modern alternatives. A laptop just cannot replace a vacuum tube oscillator for it would ruin the act of performing the piece on stage. It undermines the rhetoric and thus the intrinsic value of such compositions.

Obviously there are quite many cases were the technology is not as such at the focus of the work. The many pieces composed in live electronics using samplers for instance, can easily be performed using nowadays technology. However one has to be careful, as many composers have used equipment at or just over the border of their capabilities in which case the use of the original equipment is indicated.

3. Compositions that involve the construction of technological devices.

The devices can range from simple contact microphones and their pre-amps (David Behrman, Hugh Davies, David Tudor, Gordon Mumma, Richard Lerman, Mauricio Kagel...) , up to the most diverse sensing devices such as radar sensors (in the work of Jerry Hunt), light sensors (John Cage, Toshi Ichianagi), sonar devices (Alvin Lucier, Dieter Truestedt). Also electronic sound modifying devices, real circuits, often need to be build (Robert Ashley, Pauline Oliveros, Hans Otte). Ringmodulators and effects are examples. The performance of my own composition 'Logos 3:5' (1969) for instance, requires the performers to build an automated conducting device.

In all such cases, the realisation of the required technology should be considered to be part of the performance practice. More often than not, one has to go through the complete desciption by the author, try to fully understand (and reverse engineer) it and after that finding a working realisation with the same artistic result. I still remember some Cage performances, where Takehisa Kosugi was seated behind his performance table, handling a hot soldering iron.

The pursuit of new forms of and tools for musical expression in the second half of last century, has lead a substantial number of composers and performers to become acquanted with technology: at first mechanics and electricity, then soon after, electronics and since the late sixties, computer programming and software development.

In the post-WW2 period, we saw the upcoming of studios for electronic music all over Western Europe. Those were in general connected to broadcasting stations or universities. The Koeln studio was part of the WDR, the Milano studio oif the RAI, the Utrecht studio at the Conservatory, the Ghent studio at BRT-radio... At such institutions, it was common practice to have engineers and technicians available to work with and for the composers. In the America's this was more rarely the case. So composers that were deeply motivated to experiment with new technologies, got a stronger stimulus to study the technology for themselves. It is also of importance to mark the attention to the fact that all over the 'first' world, amateurism in electronics (in particular radio!) was highly popular. There were a lot of magazines around it, Wireless World, Circuit Cellar, Elektuur, Radio Bulletin, Elrad, containing worked out circuits and schematics. Often they even had kits available for their subsribers. Music related electronics was a constant theme covered in the magazine contributions: the theremin, electronic organs, loudspeaker enclosures, oscillators, amplifiers, mixers, filters, effects, vocoders, synthesizers, tape recorders...

Composers with a substantial background in electronics are in the field of experimental music not at all rare: David Tudor, Gordon Mumma, Dick Raaijmakers, Allan Strange, David Behrman, Don Buchla, Hans Otte, Jozef Anton Riedl, Albert Mayr, Richard Lerman, Trevor Wishart, Peter Singer, Gerhard Trimpin, Alec Bernstein, Larry Wendt, David Rosenboom, Joel Chadabe, Serge Tcherepnin, Darius Clynes, Warren Burt, Matt Rogalsky, Jacques Dudon, Dieter Truestedt, Jacques Remus, Jan Boerman, Larry Austin, David Wessel, Nicolas Collins... It was not without a reason, we ourselves allways considered some training in electronics to be an essential component in the curriculum for musical composition at the conservatory. Electronics as well as programming have been compulsary components in my teaching until I retired in 2015.

4. Compositions that depend on environmental circomstances and conditions.

A good example here is to be found in John Cage's 'Radio Music', wherefore short-wave receivers are used. Even if the difficulty in finding suitable short-wave receivers (not evident, as modern receivers use a lot of circuitry to suppress unwanted signals, circuitry that was not present in legacy receivers) is surmounted, it is a fact that the number of short-wave stations in the aether has tremendously decreased. So the multitude of morse-signals that could be picked-up up to the late seventies, is simply no longer present. Using samples in this case just ruins the piece as all adventure and all chance elements are missing. Using the FM-band instead, leads to an aesthetic that Cage would most certainly have rejected, as that radio band merely carries popular music stations.

In our opinion, such pieces may be lost forever in as far as their viable live performance is concerned. The recordings remain and the narrative around the original performances became 'history'.

In a following series of chapters, we will try to cover at least some of the most common practical issues with regard to the use and restauration of legacy electronics and technology.

1.- Tape recorders

3.- Voltage controlled equipment: synthesizers and modules

4.- Ringmodulators

7.- Effects

8.- Power Supplies

9.- Alarms: Bells, horns, buzzers and sirens [odt file] - drop this?[10.- Electromechanics: automated acoustic instruments: drop this ?

- player pianos

- novel instruments and constructions: Christoph Schlaegel, Trimpin, Jacques Remus, Martin Riches

- Expression control in musical automata

- sound art installations

11.- Interactivity: Gesture sensing [pdf file] ] drop this?

[12.- Amplifiers: voltage amp's and power amps.

13.- Sound producing devices and vibrators

- Loudspeakers (Raaijmakers, Cathy Van Eck,

- Megaphones (Charlie Morrow,

- Horns]

10.- Case Studies [to be expanded]

- John Cage

- Alvin Lucier

- Karlheinz Stockhausen

- Dick Raaijmakers

- Gordon Mumma

- David Behrman

- Robert Ashley

- Hans Otte

- Jozef Anton Riedl

- Dieter Truestedt

- Dieter Schnebel

- Michel Waisvisz

- Trevor Wishart

Research project on Experimental Legacy financed in part by the Orpheus Institute in Ghent.

Last update: January, 2023

www.orpheusinstituut.be