50 years at the Logos Foundation

Creativity is not a speciality

Carl Bergstrøm-Nielsen

Creativity is not a speciality

Western Cultural Democratisation and Logos by Carl Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Denmark

Experimental music re-discovered sound as the basis for music. And when one could do anything with the material, why should not anyone be allowed to do it? Breaking down of hierachies inside musical language is, by its intrinsic logic, bound to become paralleled by a breaking down of hierachies in music's social environment, even if this consequence is not recognised by conservative parts of music life.

This intertwining of seemingly purely musical matters with social ones is apparent in a small collection of scores called "logos anthology" (1974):

"Logos stands for: workshop for engaged (new-left) avant-garde music and mixed-media. The group was founded in Ghent 1968 by its actual leader. Although the members have changed very much, the artistic manifesto remained rather constant: no longer authoritarian scores nor relations between the members, no 'professionalism', no fixed composer-performer rules, mixed-media works and experiments, research in electronics, trying to link politics to music, emancipation of real creativity ( = negation + action), process-music instead of musical products."

5 of these keywords concern more or less directly social and political issues. At the same time, "mixed-media works and experiments" as well as "research in electronics" are in the first place "purely" musical, but they were most probably felt to be part of a progressive programme. In the same publication one could read that Godfried was thrown out of the Ghent Conservatory 1970 as a student being "anti-musical". "Purely" musical matters were perhaps not just purely musical matters for the author of the letter they sent to Godfried but could indeed appear very controversial.

It all began as early as in the 20th century's turning away from romanticism's elaborate tonality, with new liberties ensueing that could embrace complexity as well as reductionism. Before second World War, this lead in some cases to an opening of the exclusive art universe of classical music in the form of a new interest in folk music. In Hungary for instance, with Zoltan Kodaly, a whole country's music education underwent a reform as a consequence of this. However, art music remained fixed in its written details.

While Europe was still deeply concerned with re-building in the wake of the Second World War, anti-conformistic tendencies rose in the USA, and the New York school (Cage, Wolff, Feldman, Brown) reflected this in the musical domain. As documented by Charles E.Hamm, a group of Nobel Prize Winners issued in 1953 a declaration condemning the arms race which had been made possible by scientific research, and the declaration was signed by 52 scientists.Sceptical attitudes to the role of mass media and of USA's political world leadership flourished in book releases and current debates, and environmental pollution as well as blind beliefs in economic growth were criticised.1 Beatniks foreshadowed the later hippie movement.

Growing through the sixties, Europe got its own experimentalism - musically and socially. Improvisation was indeed the one, decisive discovery having the potential to push creativity out to more people. Musica Elettronica Viva made concerts with audience partitipcation at public places outside the concert hall in Rome from 1966, Group for Alternative Music did so from 1972 in Copenhagen.

Logos was part of this movement, as documented by the score anthology. The piece "Creative playing" by Moniek provided a gentle framework for free playing. The radical spirit of the day is apparent from the introduction in which she argues that some "previous contact about what to do" is nescessary to avoid chaos, even though "this is not agreeing with the liberal way of thinking about anti-authority, but since we see a danger rather than an advantage we have abandoned this principle consciously". But on the other hand, "once all cards are circulating, nothing is done to push or lead the game in one direction of the other. It is happening from every performer, and not only from those who took the initiative". Exceptions are "certain moment, on which action passes from one series of cards to another" and the conclusion. Cards may contain "missions" or graphic material. Their packs "should be in the same order, to get at least some kind of coordination between the actions of the different persions playing at a certain moment". They are supplemented by slides and passing on of objects. A classic open composition, still usable...

What was so impressive about Logos at my 1977 visit with my Group for Intuitive Music was their success with building up an institution independently of the educational ones and classical concert life. When the city of Ghent began to disappear outside the train window on the way home, one of my fellow musicians said with a very deep sigh: "It must be wonderful to lead a life so much according to one's conviction as they do".

"Filharmonie van Gent", the Gent Philharmonic, was an improvising amateur orchestra started in 1975 and was active into the eighties. No skills beforehand were required, anyone could participate. Working method was non-verbal; Godfried and Moniek just played along. In a 1981 reportage I made for the Danish Radio Moniek declared that "creativity is not a speciality". In a subsequent episode, my radio colleagues gathered two prominent music people, composer Ib Nørholm and jazz musician Ole Mathiessen in order to let them discuss improvisation issues. Nørholm questioned a perceived revolutionary musical value of improvisation, although he saw a strong need to rediscover it for musicians. Mathiessen saw improvisation rather as a technical means for the musician. The matters presented could seemingly still be of some controversy at that date.

Now in 2018 improvisation workshops are not unusual any more, and as Godfried explained to me once in the nineties, they should be specialised in order to attract the interest of participants. And many conservatories teach improvisation as well - Godfried was invited back into the Ghent Conservatory in the eighties to teach new chamber music and became a professor in 1988. Times change! One can even take Bachelor and Master of Art degrees in free improvisation in Switzerland and other places.

Democratisation has made advances and certain forms of former emancipation became normal and permanent. But let us take Charlie Bramley's warning that suppressive hierachies may persist. Improvisors, after their music form has been acknowledged to some degree, are now sometimes marketed as "top" and "renowned", thus betraying the egalitarian ideals. After not passing an improvisation examination at his conservatory in Newcastle-upon-Tyne but still passionate about improvised music he started his own workshops and founded the group "Felt Beak" in 2011.2 As in other parts of cultural life and even society in general, democratisation has developed to a certain measure in recent history, but this is not to be confused with an utopian state.

1 Hamm, Charles E.: "Changing Patterns in Society and Music: The U.S. since World War II", in: Hamm, Charles; Nettl, Bruno; Byrnside, R. (ed.): Contemporary Music and Music Cultures. Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1975. For additional writings pertinent to democratisation in experimental music, please see the present author's Experimental Improvisation Practise and Notation at www.intuitivemusic.dk/bib

2 See Charlie Bramley: "Too important to be left to the Musicians. Un-musical Activism and Sonic Fictions. in: Rothenberg, David (ed.): vs. Interpretation. An Anthology on Improvisation, Vol.1. Prague (Agosto Foundation), 2015, p. 110-18 and a different version of this article bearing the same title in: improfil. Theorie und Praksis improvisierter Musik. Nr. 78, April 2015, p. 8-10. Felt Beak may also be listened to on vimeo.

Overview of the authors

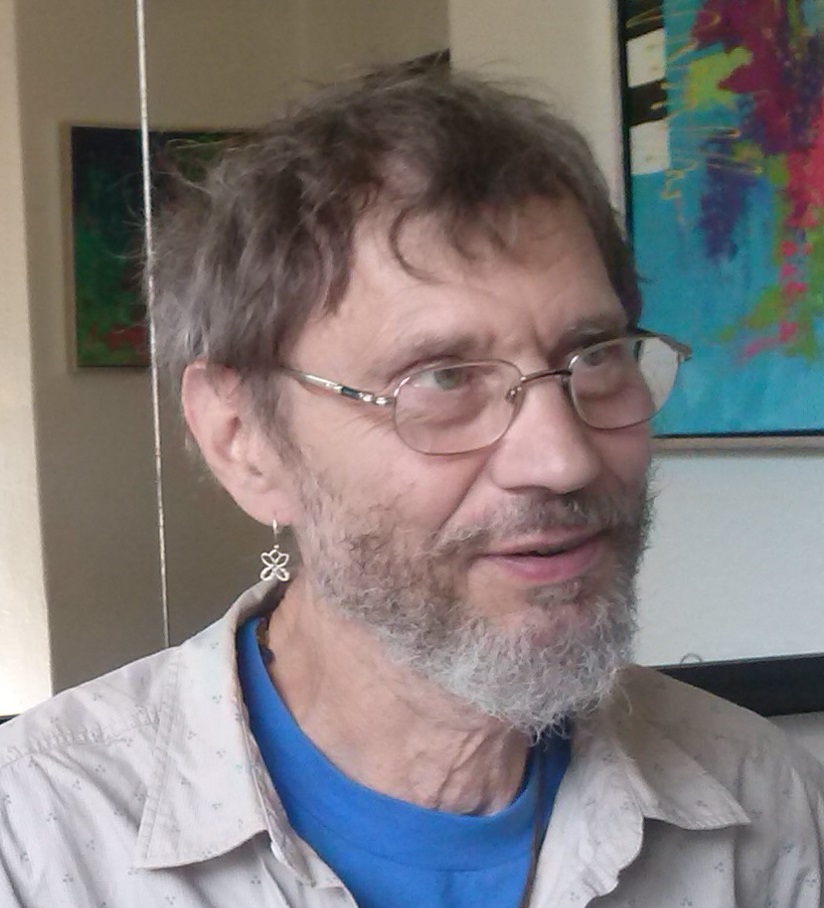

Carl Bergstrøm Nielsen

Carl Bergstrøm-Nielsen graduated from the Institute of Musicology at the University of Copenhagen in 1984 as an Arts graduate with a Master's degree and a diploma in education. Since 1983 he has been employed by the University of Aalborg to teach in the field of music therapy education, where he teaches courses he developed himself on intuitive music and graphic notation. In the 70s he was an active member of the group for alternative music, where the members all composed, played each other's compositions, improvised, published a magazine, and organized a large number of concerts. Among others Bergstrøm-Nielsen also played in the Group of Intuitive Music with Jørgen Lekfeldt and Niels Rosing-Schow (1975 onwards), ABFA with John Tchicai and Jan Kaspersen (1978-79) and Intuitive Music Group (1990 onw.)

Apart from teaching, Bergstrøm-Nielsen has made extensive courses of intuitive music at places like Stockholm, Sweden, the Academy of Music in Krakow, Poland and Kawamotocho in Japan. A key compositional idea for him is to develop means of notation that enable the performers to focus on creativity in various ways. His works often consist of complex sound textures in constant change. The composer also performs on piano, organ, French horn, various small instruments, and in addition uses his voice.