Electronics and technology appear in a great manifold of Cage's scores. It would constitute a study on its own to cover the composers complete works from this perspective, and therewith to pay attention to all problems one may encounter in attempts to perform it 'historically correct' now.

Here we will discuss just a few of his scores, where problems related to the electronic legacy can rise.

Radio Music (1956)

To be performed as a solo or ensemble for 1 to 8 performers, each at one radio.

Problem:

The numbers in the score seem to represent 'tunings' for the radio sets. No units are given however. Numbers given range from 55 to 153 and -as they are not continuous- are likely derived from a tuning scale found on a given radio set from the fifties. The numbers written in the score as tuning instructions are determined by chance operations. They neither follow the official standard for channel separation used in Europe (10 kHz), nor in the US (9 kHz). To interpret this score, first thing we need to do, is to find a correct interpretation for the numbers. Usually period radio sets had a tuning scale with tuning expressed either in wavelength (m) or in frequency units (kHz or MHz). The numbers in Cage's score suggest a scale encountered on a radioreceiver like this one:

Thus it is suggesting the radiobroadcast AM band, with frequencies expressed in 10kHz units. However, therewith the problem is not solved at all: recordings from period performances, reveal that short wave radio was used: we hear Morse signals and all audible artifacts so typical for short-wave bands. Further evidence for this is in the fact that the radio AM band was reserved for national radio stations and not legally allowed for use by amateur Morse broadcasts. But, if we have a close look at period radioreceivers, we will notice that the tuning scale often has many numbers printed on it. The radio on the picture, has a 0 to 10 scale, below the large-number scale. The largest set of numbers, standing for the wavelengths of common radio stations in the AM band. A rotary switch (most often) allowed the user to switch the radio receiver to different frequency bands: The long wave range as well as one or more short-wave ranges.

Cage does not give even the slightest hint as to the frequency range to be used. The only other knob he has instructions for, is the volume controller. This fact in any case, already entails a hint for the equipment to be used: portable self-contained receivers and not tuner's fed into a central mixing board. So there should not be any external amplification.

If attempting to perform this piece first thing to be done would be to recalculate all numbers/tuning in the score such as to correspond to the scale used by the radioreceivers at hand. Dividing the given scale proportionally to the number range given in the score is one solution, a better idea might be to use a length of white sticky tape, cut to the length of the physical scale, and copy Cage's range with marks on it. Then, just stick the tape on the receiver scale and perform the piece from the original parts.

A technical detail, however with high relevance to performance practices for this piece (and other pieces using radio receivers) is that old radio receivers rarely had a squelch circuit. This is a circuit that suppresses automatically all noises that normally are received when the radio set is not exactly tuned to the carrier frequency of the broadcasting station. On almost all multi-band receivers produced after the vacuum tube era, such circuits became universal. Of course, on sets with such circuits, most likely a performance of 'radio music' could likely lead to nothing but silence, as the composer doesn't want the performer to adjust the tuning for good reception. The only thing he is supposed to do is setting the dial for the frequency and turning the volume all the way up, regardless what the receiver spits out.

In our opinion it is and remains mandatory to use, if not period radio receivers if still in working condition, than at least equivalent modern ones. It is not very hard nor expensive to build simple short wave receivers and one can find literally thousands of proven designs on the Internet. They are even available as DIY kits. At Aliexpress, we easily could find even kits using vacuum tubes. We have yet to try it though. As there are much more sources of aether-smog nowadays than in the fifties, we would advice to use reasonably long antennas. Modern world-receivers are to be avoided, as more often than not they are way too sophisticated: they have autotune facilities and digital frequency synthesizers, automatic volume control, squelch circuits and automatic interference suppression. Moreover, they rarely have a tuning dial and instead use a numeric keyboard to enter the required tuning frequency.

So far, we have been talking about the technical aspects of performing 'Radio Music' from the performers perspective. But, there is a second maybe even more prohibitive problem, unrelated to what a performer can or could do: the aether and the radio signals occupying it itself. The short-wave bands as well as the AM broadcast MW band, are more and more abandoned or, used for all sorts of radio beacons, digital and encrypted transmissions. In other words: the entire radio environment has changed tremendously. It is pointless to attempt to re-create the aether as it was in the fifties, filled with Morse signals and short-wave stations with national news from all countries in the world. There really wasn't much music to be found there, as the possible quality that could be obtained in those radiobands was way too low for even recreational pleasure.

One may get seduced into trying to perform this piece, using modern portable radios using the FM band. We are absolutely certain that this entails a complete misunderstanding of Cagean aesthetics. The piece would sound more or less like a John Zorn collage, because on a modern FM receiver, stations always come out right and thus you would get mostly commercial and entertainment musics, as that is what occupies this band. Also, as FM radio covers only an area of at most 50 km around, the adventurous character of tuning into remote radio stations, evaporated. Alvin Lucier in his book 'Music 109', reports about Cage at a performance with a radio set, happening to hit Radio Vatican, and got the pope speaching for a while...

As a conclusion, we are convinced that a historical performance in the sense of a recreation of this piece is impossible. It would never sound the same as in the time of its conception. At the other end one may argue, that the changes the piece undergoes by historically informed performance of it, are an intrinsic part of the Cagean aesthetic. It we extrapolate it into a further future, at the end, we may end up with nothing but silence. We are certain Cage would have loved that consequence.

There are other pieces by Cage where radio receivers are required in the score: In 'Water Walk' (1959), five portable radios of inferior quality are prescribed. No further specs nor details given. The score just specifies them to be switched on and off at given times.

The oldest Cage piece involving radios is 'Imaginary Landscape #4' (1951), scored for 12 radios and 24 performers with one conductor. Each radio requires two performers to use it: one for tuning and the other for the amplitude and timbre changes. This is the first composition wherein Cage radically tries to detach from his own work and wherein he attempted not to have any control on the composition. (Cf.. his book 'Silence', p.57-60). In reference to this, Cage commented: "It is thus possible to make a musical composition the continuity of which is free of individual taste and memory (psychology) and also of the literature and 'traditions' of the art. The sounds enter the time-space ... centered within themselves, unimpeded by service to abstraction". Performances of this piece we listened to, -all recordings we could find data from the 21st century- reveal that the AM radio band was used. In-between-stations noise was anticipated and is an essential part of the piece. In all too many recordings this is missing or way to damped. Hence, here again, the use of modern radios with automatic tune-adjust and squelch circuitry is inappropriate. The 'six transistor' small radiosets cheaply produced and omnipresent in the sixties, would be a good choice. Original portable radios from around 1951 would all be vacuum tube types. If they would still work at all, for sure the required batteries to feed them are since long no longer produced. They needed a hefty '90V anode battery' as well as a 1.5V battery for the filaments. The 90V battery is obviously the problem here.

The score is prefaced by an extensive explanation on the indication of duration's, station tunings, dynamics (numbers ranging from 3 to 15, 3 being turned on but inaudible, 15 being maximum volume).

Cartridge Music (1960)

In a footnote in the score, Cage writes: 'A cartridge is an ordinary phonograph pickup in which customarily a playing needle is inserted. Instead of a playing needle, any object that will fit into a cartridge may be inserted (e.g., a coil of wire, a toothpick, a pipe-cleaner, a twig etc.).

Turntables, certainly those commonly used in the sixties, are harder and harder

to find. The cartridge in an old turntable is about the very first component

to fail... So hunting for well functioning old phono cartridges may have become

quite an undertaking by now. Here are some pictures of period-cartridges of

the kind used by Cage:

Notice that these cartridges

even have a small screw wherewith the needle is to be secured in the cell. This

makes attaching other objects as Cage suggests for this piece, an almost trivial

undertaking. Also note that all such cartridges are mono, as they date from

before the time stereo records were introduced. Cartridges from the mid-sixties

look like this:

Mono cartridges became very

rare and only made for the reproduction of older gramophone recordings. And

herewith, we enter the early seventies:

As

one sees right away, its already a bit more tricky to secure other objects.

Still it's feasible with a bit of handiness.

Good quality modern cartridges as made by Shure, Pickering, Orthophon and the

like, are still made today in answer to an unexpected popularity of vinyl in

some circuits. These high quality and expensive types -always stereo- are very

hard to use for performing this Cage piece because they are very fragile and

too light. It's difficult to replace the stylus / needle assembly by inserting

other objects. In no time, the cartridge is ruined by doing so. Here a picture

of a Shure cartridge, the needle removed:

If it appears impossible to obtain original cartridges, there are acceptable

alternatives, requiring some construction and simple circuit building. Piezo

electric material can be used, in combination with a suitable preamp. Here is

a picture of a very simple yet sturdy construction, using a Piezo disc, clamped

in silicone rubber and provided with a screw mechanism to attach all sorts of

objects: And this

is a circuit for the buffer preamp to go with it:

If original cartridges are used, of the magnetic type, one should use a circuit

like this one:

If original cartridges are used, of the magnetic type, one should use a circuit

like this one:  This is designed and drawn for a stereo magnetic cartridge, providing in proper

equalization as specified in the RIAA standard for phonograph recordings. Modules

with spare preamps of this type are still available on the market, one of the

reasons being that many modern amplifiers do not have the required inputs anymore

for connecting turntables.

This is designed and drawn for a stereo magnetic cartridge, providing in proper

equalization as specified in the RIAA standard for phonograph recordings. Modules

with spare preamps of this type are still available on the market, one of the

reasons being that many modern amplifiers do not have the required inputs anymore

for connecting turntables.

In the score instructions Cage is very clear about the idea that each cartridge and player should have its own amplifier and loudspeaker in close proximity. The amplifiers used should have individual volume as well as a single sound control. The latter used to be a simple low pass filter. The control knobs must be of the rotary potentiometer type, as a scale for them to use is included in the score. The amplifiers are preferably to be setup around the audience. So, the use of mixing desks is certainly a wrong practice for this piece. It kills the sonic transparency of the piece.

A good source for information with regard to old phono-cartridges is: James Moir, High Quality Sound Reproduction, ed. Chapman & Hall Ltd., London 1958.

Bird Cage (1972)

Twelve tapes to be distributed by a single performer in a space in which people are free to move and birds to fly

Apparently, the tape recorders Cage envisaged for this piece are mono machines, nominal speed 7 1/2 ips ( 19 cm/s), each with an amplifier of its own. Cage explicitly states that other machine speeds may be used. The performance, for and by a single person, consists of manipulating the tape recorders: switching on and off, swapping tapes, rewinding... Also it is clearly not meant to be a 'concert' piece but much rather what is called nowadays an 'audio art installation' or a soundscape.

Alternative technologies that can be used here: analog cassettes, DAT tapes. Digital computer based technology is not appropriate for performances here.

Telephones and Birds (1977)

For three to perform.

Next to calling for tape recorders -their noises are declared explicitly part of the performance- this piece calls for telephones, yet another technology that has changed substantially over time: dialing a number, automated answering machines, ring-tones, taking up the horn... all these once so typical sounds for telephony have changed. Also the list of phone numbers, 17 USA numbers for the National Rare Birds Alert Network, specified in the score has not a single number that is still connected now.

Trying to perform this piece with period telephones is vain, as technology made old phones obsolete. They can no longer be used to connect to the phone network. This piece, if one judges it worth the effort, ought to be recomposed. Using chat sessions and the Internet may be a valid way to go. However, in performing, it should be made clear to the public that it is an adaptation and that the performance as presented may deviate heavily from any period performance.

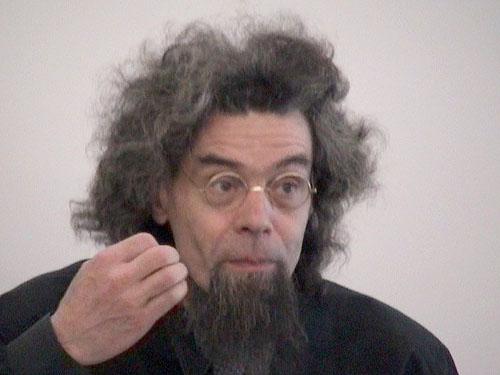

Next to the scores explicitly calling for electronic and technical devices, Cage has published a whole lot of scores and score materials, wherefore electronics of some kinds seem particularly indicated. The series of 'Variations' is a good example. In his own performing practice, simple electronics have more often than not, been present. The many concerts he gave as a composer/performer, very often were collaborative projects with soulmates such as David Behrman, Robert Ashley, Alvin Lucier, Takehisa Kosugi, Frederic Rzewski, David Tudor, Gordon Mumma and a few more. The staging for most of them consisted of one or more tables filled with electronic devices. We remember assisting to one of his concerts in Los Angeles in the eighties, a production with Merce Cunningham, where we saw Takehisa Kosugi handling a soldering iron on stage as part of the performance... Contact microphones, small mixers, modulating devices, gating devices, photo cells triggering oscillators, tape recorders, oscillators, radio circuitry, amplifiers as well as toys and gadgets formed the gamut of sound sources for the performances. We do not remember where the picture comes from, but it gives a pretty good impression of the stuff used. We see Frederic Rzewski and John Cage performing one or another Cage piece:

A device of particular interest Cage used (a/o. reported by Alvin Lucier) is the throat microphone. We state it as of interest, because some other composers also used and prescribed these special microphones in their scores. The most wellknown piece here could very well be 'Maulwerke' by the German composer Dieter Schnebel. But we have also seen it used on stage by artists from the sound poetry scene, such as Henri Chopin, Lilly Greenham and Gust Gils. Throat microphones in origin are strictly military devices. Their invention and application was an answer to the problem of pilots in military aircraft (bombers and suchlike) in communicating over their radio system with commanding ground. Normal microphones, even placed extremely close to the mouth of the pilot, were pretty useless as the sound level of the engine in the cockpit made it impossible for a voice to get over it. Thus the idea of picking up the vibrations of the larynx directly arose. In fact it can be considered to be a contactmicrophone, designed to pick up larynx vibration as conducted through the bony structures in the human neck. Many models and types were made throughout world war two. Carbon mikes, electromagnetic types, crystal type etc... Do not expect a throat microphone to deliver a clear and nice vocal signal! Even understanding speach with it, requires a lot of practice from the side of the listener. This is because the articulation through the mouth cavity is largely absent in the signal. Throat microphones can still be found in the catalogues of professional microphone manufacturers such as AKG. Here are some pictures of the historic types as used by composers and performers:

This is an electromagnetic type:

Here we have a carbon type: In

order to give out a signal, it needs a 1.5V battery. Carbon mikes, being vibration-dependent

resistors, do not give out a signal unless fed with a current. The output of

both these types is balanced and low impedance, thus they can be connected straigth

into any microphone input on an amplifier or mixing desk.

Throat microphones can still be found on flea markets and in army-stock warehouses.

For interactive applications -more specific, for productions with Merce Cunningham and his dance company- Cage has been using photocells. He nowhere gives more specifications about them, but we are sure he confined the technical details to his collaborators some of which were very knowledgeable in electronics: David Behrman, Takehisa Kosugi, Gordon Mumma to name just a few. Although one may encounter original photocells from the fifties, it will be of little use to try them out: photocells , as used for picking up optical sound in film projectors with an optical soundtrack, are gas-filled vacuum tubes. They are severely sensitive to aging and the sensitivity of them now, is -after our own findings and measurements- worse than 40dB down. In the industry gas filled photocells have since long been replaced with by far superior semiconductor types. Installations and scores mentioning photo cells should be re-engineered with a good understanding of the function they fulfilled in the period-equipment or setup. For many applications, LDR's can be used although it must be said that in as short time from now, they will also become obsolete and their production even outlawed as they contain a substance toxic to the environment: cadmium sulfide. Phototransistors can be used, but their use is a little more involved: they need some kind of a circuit and their output is a voltage or current. Often, for instance if the photo cell is used as a sound generator, picking up amplitude modulated light, an excellent solution consists of using a solar cell. These are in their common appearance in general way too large, but it's quite easy a break off a small part, and solder connections to it. Note that a special solder must be used to do this! Solar cells thus prepared, can be connected straight into an audio mixer. The French artist Jacques Dudon uses them as the core of his optophonic concerts and installations.

For this piece, Alvin Lucier used ultrasonic transducers of the kind that emit a strong and short burst of ultrasonic sound. After the end of the burst, a timer is started in the circuit. That timer is stopped the moment that an echo is received. The time interval is than proportional to the distance from transducer to object that caused the echo. Lucier, for this piece, was not interested in the function of the device as a distance measurement thing, but much rather by the fact that, if the bursts where strong enough, the echo could even heard by human ears. This is of course caused by the fact that at the onset of the burst -normally a finite number of complete sinewave periods- is a spike and thus a board spectrum signal. Even though the frequency is ultrasonic and as such inaudible for humans, the start of the series of pulses can we heard as a click or a spike. Such spikes can be used to get echoes from objects not to far away, as long as the are reasonably reflective. That's exactly what Alvin Lucier is exploiting in this piece. In his own descriptions for 'Vespers', he mentions the device is a Sonplus [check] , experimental prototype one of a kind. He also affirms he didn't want to let other people used it as he considered in irreplaceable. As we did quite extensive research in to area of ultrasonics, we found that in fact there are quite a few such devices on the market (Pepperl+Fuchs) and, moreover, it's not extremely difficult to build such devices, if only the burst property is of interest.

'I'm sitting in a room'

This piece could also work with other technology, as the gradual deterioration of the signal is only to a certain extent caused by the lower S/N-ratio of tape recorders as compared to pure digital recording devices.

'Brainwave pieces'

Gordon Mumma

mesa

David Tudor

Although David Tudor as he performed, had almost invariably a stage full with a diversity of electronics devices. Much of it, he designed and made himself. He used to house his circuits in plastic household boxes. However, he kept his circuits secret and thus it becomes pretty difficult to reconstruct. He clearly didn't want others to perform as he did. It's not that he wasn't communicative, but he simply didn't disclose nor document his musical tools. Even his close friend Alvin Lucier wittnessed this. (Lucier, Music 109, p.62-63). We know that ringmodulators were very often present in his set-up and that many of his modules were very similar to what can be found in a lot of modular synths from that period: VCO's, VCA's VCF's, oscillators of different kinds and waveforms...

David Behrman

'Runthrough'

As described by Alvin Lucier (Music 109, p.77) , this improvisational piece makes use of photo resistors placed into empy tin cans of Campbell Soup. The players use flashlights to cause sounds to spin around on a four-channel loudspeaker system. Voltage control is used to steer modular synth components of his own invention and making.

wave train

Robert Ashley

|

This paragraph is part of a research project on Experimental Legacy financed in part by the Orpheus Institute in Ghent. www.orpheusinstituut.be |